#11 The three kinds of defense tech revolutions

Lessons from history for the future force

How do militaries adapt to technological revolutions? History suggests three models.

This week on Integrated Strategy we’re taking a high-level look at those models. The following note is adapted from a longer essay with Harry Halem in the current issue of the Texas National Security Review, which in turn is adapted from our book The Arsenal of Democracy: Technology, Industry, and Deterrence in an Age of Hard Choices. (Get your copy here.)

We apply these lessons to cover the entire U.S. military deterrence system against China—in an overview short enough that you can grasp it quickly.

Key takeaways:

Our margin of deterrence against China is rapidly shrinking.

The problem isn’t a failure of US technological innovation. It’s that the allied defense industrial base (DIB) is struggling to field and sustain cutting-edge capabilities at scale, at speed, and under pressure.

The United States must urgently expand its defense industrial base, but it will fail unless it works in coordination with allies.

The top priority: systemic vulnerabilities that represent our fastest path to defeat: our increasingly brittle scouting (C4ISR) and logistics networks.

The most time-sensitive industrial investments: munitions, drones, and submarines.

Stabilizing the negative trend in the military balance does not require a doubling of the defense budget. We need a whole-of-system effort by the Pentagon and Congress, a one-off chunk of money to recapitalize the right parts of the DIB, and a political mandate to make hard choices.

The Timing and Nature of Technological Offsets

China’s military modernization is designed to undermine the foundations of American military superiority. Washington and its allies must therefore pursue an industrial-technological transformation to offset China’s strategy.

History offers no ready-made formula, but it is useful for framing current choices and understanding their potential costs and benefits.

Option 1: The “Dreadnought Offset”

This is the boldest approach: wipe the slate clean by betting on a high-tech bundle to completely outclass current standards.

When the British Royal Navy deployed the HMS Dreadnought in 1906, it instantly rendered every existing battleship obsolete—including Britain’s own. When successful, a Dreadnought offset can neutralize an adversary’s quantitative momentum by making existing investments irrelevant.

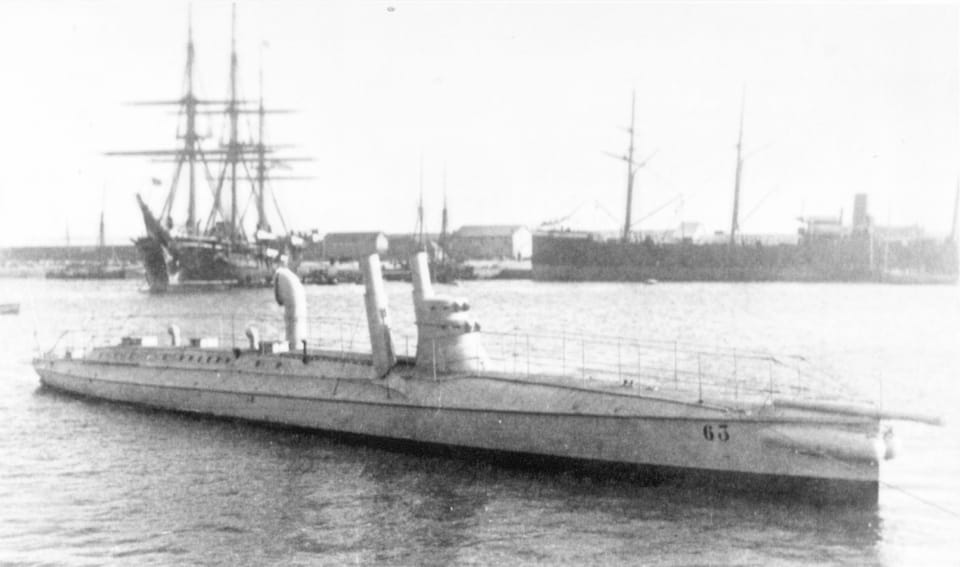

HMS Dreadnought upon its commission, 1906

The risk: if implementation slips, the transition period can create soaring costs and acute vulnerability.

The US military today carries the battle scars from a messy attempt at a Dreadnought offset. In the 2000s, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld sought to transform the Joint Force by replacing heavy land forces and mass with airpower, precision, stealth, and autonomous systems.

It was a daring bet on largely the right technological trends, but the initiative was poorly executed. The Joint Force failed to coordinate the offset effectively, partly because the Global War on Terrorism diverted bureaucratic bandwidth. Key programs arrived years late and grossly over budget. By the time the Joint Force began to reap the fruits of Rumsfeld’s vision—nearly twenty years later—China was already implementing the same solutions and fielding new tools to offset America’s advantages. This is a key reason why the Pentagon has resisted the current defense tech revolution.

Option 2: The “Torpedo Boat offset”

The other extreme. Integrate new technologies with legacy platforms to make the existing force more effective.

In the late nineteenth century, many strategists believed that the small, cheap, mass-produced torpedo spelled the end of the large, expensive battleship, predicting that it would equalize the Royal Navy’s structural advantages. This debate echoes current discussions about emerging threats from drones.

A French type 63 torpedo boat at Toulon, 1884

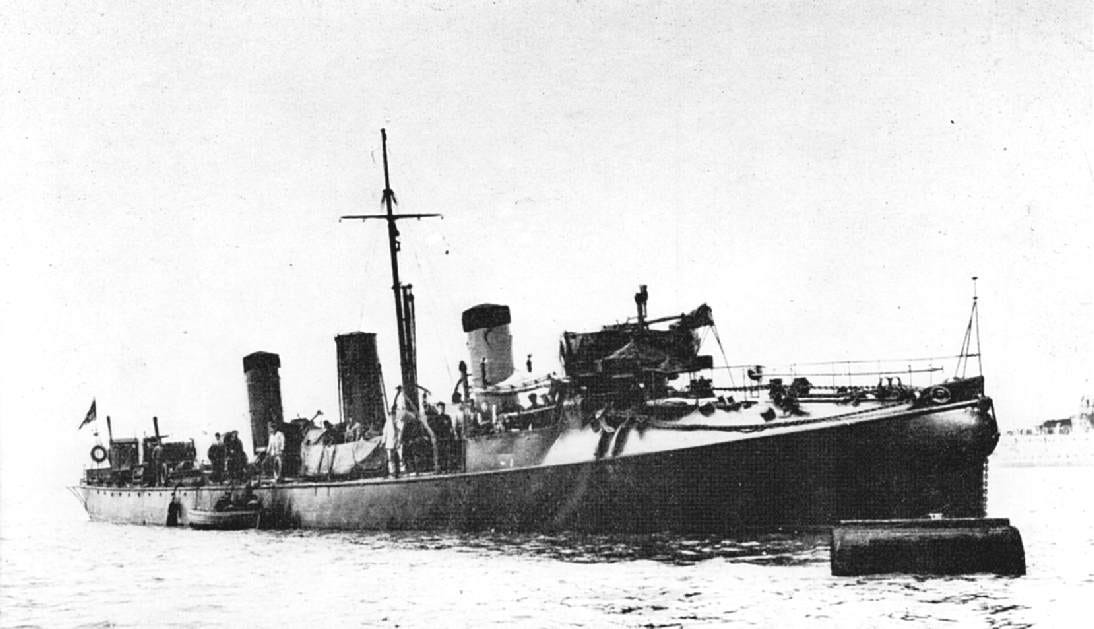

But the torpedo’s proponents were wrong. Big navies countered the threat by creating “torpedo boat destroyers”—the progenitors of today’s guided-missile destroyers. Working together with battleships, they could easily destroy the small torpedo-laying vessels—including by using torpedoes themselves.

The result was a more complex but ultimately more capable naval system that remained the standard for fifty years.

A British Havock-class torpedo boat destroyer, 1893

“Historical military offsets reveal a clear pattern: Industrial capacity, technological R&D, and doctrine must be aligned over time and across institutions.”

Option 3: The “Second Offset” model

This is the middle path. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Carter and Reagan administrations placed command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) at the center of US military transformation.

The Second Offset leaned heavily on legacy platforms—but built a new enabling layer that transformed how they were used. This enabled radically new operational concepts. For example: GPS.

The key to this model is mastering coordination between technological development and doctrinal innovation so that the new layer can integrate seamlessly.

Conclusions

Historical military offsets reveal a clear pattern: Industrial capacity, technological R&D, and doctrine must be aligned over time and across institutions. History offers no off-the-shelf model to copy, but successful transformations require integrated strategy and policy coordination.

No single actor—not the White House, the Pentagon, Congress, industry, or allies—can dictate terms. These parties must find ways to work together, starting with a common operating picture of the deterrence system. Our work aims to provide that picture.

To learn more about how these lessons apply across the deterrence system, from space to submarines, read our full TNSR piece here.

Also much more on these topics in my forthcoming book Defending Taiwan: A Strategy to Prevent War with China, out April 14 through Oxford University Press. You can pre-order here and get 30% off with the code.